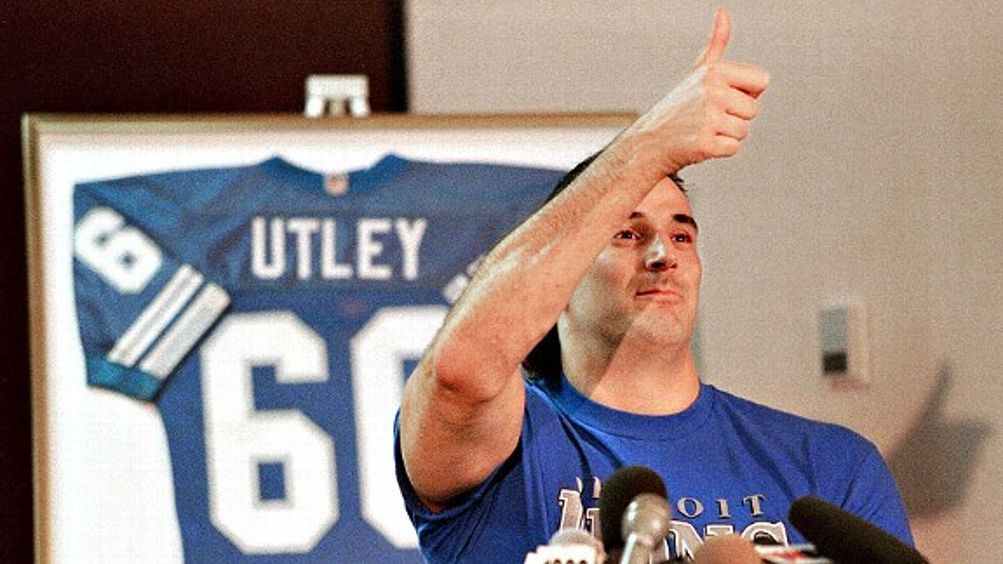

AP Photo/Mike Fiala

A writer speaks with Mike Utley to see if a positive gesture lets fans off the hook

By Jordan Ritter Conn

Near 7 p.m. on November 17, 1991, Mike Utley walked onto the turf inside the Pontiac Silverdome. Utley, the Detroit Lions’ starting right guard, had spent three quarters trying to clear paths for Barry Sanders, but he had little to show for his efforts. Sanders had been contained. The Lions trailed the Los Angeles Rams, 10-7.

So with the fourth quarter set to begin, Utley approached the line of scrimmage with malice. By any means the rules allowed, Utley thought, he would brutalize whichever man lined up across from him. Utley had long ago made peace with the savagery of his sport. The man opposite Utley had chosen to be there. Utley’s job was to punish him for that choice. There were no innocents in the trenches. You both inflicted pain and endured it. Utley preferred to inflict.

Utley crouched into his stance. David Rocker, a rookie out of Auburn, lined up opposite him. As the ball was snapped, the two men collided. Lions quarterback Erik Kramer dropped back and threw a quick pass toward wideout Robert Clark. As the pass sailed over Utley’s head, Rocker leapt and tried to deflect it. Utley lost his balance and slipped forward. As Rocker returned to the ground, he landed on Utley, forcing him downward. Utley tried to use his arms to break the fall, but he was too late. His head crashed into the turf.

Clark caught the pass for a touchdown and gave Detroit the lead. But as the crowd erupted, Utley lay motionless. Immediately, he feared the worst. Like most football players, Utley had been dinged before. He’d suffered stingers that sent burning sensations through his arms and legs. He’d been knocked out. But always, he’d been able to move. “I always told myself, ‘A man walks on the field, and a man walks off the field,'” Utley says now. “So I promised myself, no matter what, I would always walk off the field.”

After lying still for several minutes, Utley was lifted onto a stretcher. As medical staff removed him from the field, teammates came over to give encouragement, and the crowd roared in support. Utley, fully conscious but still immobile, struggled to communicate. “I wanted them to know, Mike Utley hears you,” he says. Though he was paralyzed from the chest down, Utley still had use of his hands. He balled one into a fist and lifted his thumb, offering a thumbs-up. His teammates clapped. The fans screamed.

Inspired by Utley, the Lions dominated the fourth quarter, winning 21-10. Utley was taken to a hospital, and he underwent surgery. Twenty years later, he still dreams of a day when he can walk off the field.

Utley’s thumbs-up gesture — rather than the ferocious way he disposed of defenders — became his legacy in football. No one can say for certain that Utley was the first person to give the thumbs-up after a spinal injury, but no one is more closely associated with the act than him.

The Lions dedicated the rest of their season to Utley, wearing stickers with his jersey number on their helmets and imploring each other to win games “for Mike.” Before the Thanksgiving Day game, offensive tackle Lomas Brown gave an emotional speech about Utley, and as he spoke teammates and fans looked on — some eyes wet, all thumbs held high.

I was 6 years old on the day Utley went down, and I didn’t learn that he was the presumed originator of the thumbs-up until recently. But I’ve long been struck by the way the act has embedded itself in the culture of the game. No boy dreams of lying on the field, waiting for paramedics to carry him to the sideline. But when that moment comes, a player’s response is instinctive. If he can, he flashes the thumbs-up. Like dancing in the end zone or painting on eye black, the gesture has become a football reflex — pioneered by pros, furthered by collegians, and now internalized by kids across the country.1

“When a guy goes down with that kind of injury, that’s the first thing you look for,” says Eddie Canales, who runs the Gridiron Heroes charity, which provides support for high school players who’ve suffered spinal injuries. The basic message is simple. “If a guy can move his thumb, that’s a sign that some signals are going through,” Canales says. “If you don’t see that, you start fearing the worst.” But when the thumb goes in the air, the fans rejoice. The player can move. Everything will be fine.

Only sometimes, it won’t.

Near the turn of the 20th century, on-field player deaths were common. In 1905, at least 18 players died during games. The legalization of the forward pass and other reforms helped curb football’s violence, so the modern NFL has never had a tragedy equivalent to Dale Earnhardt’s death — a moment that forces fans and participants to confront the horror their sport can create. NFL players have died during or immediately after games, but those deaths were the results of preexisting conditions rather than injuries sustained during play.

That doesn’t mean, however, that football no longer kills people. “Now, it’s not an instant death,” Dave Pear, a former Tampa Bay defensive tackle, told the New Yorker. “Now it’s a slow death.” The sport’s most damaging effects come long after a career ends, shedding years from a man’s life with maladies spawned by the game’s trauma. Studies have shown that, for players with more than five years of NFL experience, life expectancy ranges from 53 to 59 years, depending on the positions they played.

Earnhardt’s death (as well as those of other drivers) prompted everyone involved in auto racing — from drivers to owners to fans — to reevaluate the danger of their sport. After a driver dies, there is little room for equivocation. A man is dead. Racing killed him. Any defense of the sport must account for that fact.

But here’s where NASCAR and the NFL differ: Racing is about risk. Football is about violence. In football, there isn’t a chance players will be hurt. There is a guarantee. Football kills its players, on every down of every game, but death doesn’t arrive until years after they’ve disappeared from our television screens.

The moments following a spinal injury represent the closest football ever comes to an Earnhardt moment. The player’s limbs go limp. He looks less like a world-class athlete than a corpse. The moment is significant not only because it is catastrophic, but also because it represents one of the few times when football’s brutality becomes impossible to ignore. Everyone in the stadium — players and coaches, fans from the front row to the upper deck — must look on, wrestling with the damage the game has done.

Even on TV, these moments are wrenching. So to find out how it feels in person, I called Ken Dallafior, an offensive tackle on the ’91 Lions and one of Utley’s closest friends from the league. “A moment like that makes time stop,” he said. “We all recognized the severity of it. It makes you take inventory of all things, of your priorities. That moment is not about football.”

Dallafior, of course, means that it’s a moment to focus less on the result of the game than on the safety of a human being. But that’s precisely why the moment is about football. As a fan, it’s a moment to consider the violence of the game, a moment for uncomfortable thoughts, a moment for reckoning with the reality that we support a game that occasionally must pause so a human body can be swept away before the spectacle can resume.

Sometimes, just as these uneasy thoughts take hold, the player lifts his thumb. It lets us know he has feeling in his extremities. But it also conveys more. “As a football player, when I saw Mike do that, I could see that he was setting an expectation for us,” said Dallafior. “He was saying, ‘Go win this game. Go kick somebody’s ass.'”

The players resume playing. The fans resume cheering. Rather than being discomfited by the effects of the sport, we are inspired. With his thumb stuck skyward, the player lets us off the hook.

I contacted Utley last month, and he called me on a Friday morning from his home in Eastern Washington. These days, Utley said, he wakes up every morning before dawn. He lifts weights and participates in physical therapy. He raises money to fight paralysis. He does it all from a wheelchair, and he does not complain.

He goes skiing. He skydives and skin-dives. He says he has no regrets. Well, he wishes he weren’t paralyzed, but as far as the choices he’s made, he wouldn’t change a thing. In 1992, he started the Mike Utley Foundation, which raises money for research and education regarding spinal cord injuries.

Someday he hopes to return to Detroit and go to Ford Field — the stadium that replaced the Silverdome — and walk off the field under his own power. He believes that day will come.

“I know that everything I’m doing is getting me closer to that goal,” he said. “But damn, I don’t know what I’m missing. I’m looking for that key ingredient. Maybe it’s finding the right researcher, the right surgery. Maybe it’s finding the right therapist, the right nutrition for regeneration. I don’t know what it is, but God willing, I’ll live long enough to find it.”

I asked about the meaning of the thumbs-up. Does it give permission to move on? Yeah, he said, it does. But he thinks that’s a good thing. He certainly doesn’t begrudge his teammates for playing without him, or the fans for cheering them on. “I’m still pissed they didn’t win the Super Bowl,” he said. “I could have had a Super Bowl ring.”

So if it’s permission to carry on, then does the thumbs-up let people off the hook? For Utley, the question is irrelevant. Because if you’re talking about culpability, then you’re talking about victimhood, and Utley refuses to see himself as a victim. “Here’s the thing you have to think about,” he said. “I chose to be on that field. I chose to cross that line. I chose to listen for the snap count. You go back and watch it. As [quarterback] Erik Kramer starts moving his foot, and as that ball hits him in the ass, my right hand and foot are moving backwards. The other linemen have not moved yet, but I’m already moving. I chose to play this explosive game, to hit someone so hard their eyes roll back in their head. I chose to be there. I chose all of it.”

Utley won’t blame the game. He relished the violence, so he lives with the consequences. To blame football is to deny Utley control of his own life, and every success he’s had — from the moment he first stepped on the Silverdome field to the moment he uses his arms to vault himself into a Ford truck each morning2 — is a direct result of Utley’s belief that he controls his destiny. There is room to debate the morality of football, and there’s a time to consider our role in promoting barbarism as a form of entertainment. But maybe I was wrong. Maybe the thumbs-up isn’t about us at all. “That moment,” Utley said, “that was me making a promise to myself and to everyone else. That’s me saying I will not quit. I will not give up. I will be back.”

Twenty years after he raised his thumb, Utley insists he’ll keep working toward the day when he can walk off the field. In the meantime, we’ll be sitting in front of our televisions, cringing as we watch more injuries, then waiting to see the fallen players’ thumbs, imploring them to signal that everything will be OK.